CYANOBACTERIA

Cyanotoxin monitoring in the Lower Wolastoq [St. John River]

Since 2019, ACAP Saint John has been working with a collaborative group of watershed organizations, researchers, and government to advance our understanding of cyanobacteria within the Wolastoq watershed. This began with the deployment of passive collectors within the river and has since pivoted to the use of cyanotoxin detection kits to monitor for the presence of cyanotoxin at many sites throughout the watershed. In addition to the monitoring, ACAP Saint John has been working with our partners to increase public awareness and understanding of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins - to learn more about cyanobacteria continue reading!

Read below to learn about cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins and risks to you and your pets.

NEW! Want to learn even more about cyanobacteria?

Check out our newly released cyanobacteria training module on the Atlantic Water Network’s wet-pro training site.

This project was undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada through the federal Department of Environment and Climate Change Canada and through the New Brunswick Environmental Trust Fund.

CYANOBACTERIA - Two different types of threats in and out of freshwater

There are two types of cyanobacteria blooms: those you can see on the surface of the water commonly referred to as surface blooming cyanobacteria and those found in clumps or mats on the bottom of waterways called benthic cyanobacteria. Each type has a different impact on human and animal health.

Since some species of cyanobacteria can make toxins that are harmful to humans, the Government of New Brunswick will issue an advisory for bodies of water with a confirmed presence of a cyanobacteria bloom. Advisories are issued to inform local recreational water users to help make informed decisions on water use in the affected area and to be more aware to look for the formation of highly visible blooms and scum.

Read more to find out about cyanobacteria and what to be aware of.

What are Cyanobacteria?

Cyanobacteria, commonly called blue-green algae, are a type of bacteria. They share some characteristics with algae, which is why they have been called algae for many years. Cyanobacteria are naturally present in rivers and lakes and have existed for billions of years. Cyanobacteria are not normally visible, but with the right conditions (temperature, sunlight, flow, and food - nutrients) populations can grow quickly and clump together to form what is called a bloom.

Cyanobacteria feed and grow on nutrients from decaying organic matter (like aquatic plants), in runoff from the land, and in sediments at the bottom of the water. Many human activities can cause an increase in nutrients entering our lakes and rivers. These activities include:

runoff (both soil and nutrients) from lawns, agricultural land, and forestry operations

faulty or improperly functioning septic systems

excess use of lawn and garden fertilizers

use of household and industrial cleaners that contain phosphate

Cyanobacteria blooms typically occur in warmer months starting in late spring to early summer. However, cyanobacteria are present year-round, and blooms or mats are possible at any time.

Example of a dense surface bloom in a New Brunswick lake.

Not all Cyanobacteria are Toxic

Not all cyanobacteria are harmful, only some cyanobacteria species produce toxins. These toxins are called cyanotoxins and are harmful to human and animal health. It is not possible to tell the difference between toxin-producing and non-toxin-producing blooms by looking at them.

Cyanobacteria that produce cyanotoxins can cause skin, eye and throat irritation. More serious health effects such as gastrointestinal illness can occur if toxins are ingested when swimming or enjoying other recreational activities. Children and immunocompromised individuals have a higher risk for severe health effects. Dogs have the highest risk for toxin exposure because they are more likely to ingest cyanobacteria.

Most commonly surface blooms produce microcystin which is known to cause skin irritation, gastrointestinal illness, and can cause more severe illness if ingested.

Benthic cyanobacteria can create neurotoxins called anatoxins. Human poisoning is very unlikely as most people will not ingest mat material. These toxins can cause skin irritation, gastrointestinal issues and/or numbness or tingling of fingertips and around the mouth if ingested.

What to learn more about cyanobacteria toxins?

Check out the Grand Lake Jemseg Watershed Association webinar with Dr. Janice Lawrence from the University of New Brunswick.

Surface Blooms and Benthic Mats

Surface Blooming Cyanobacteria:

Surface blooming cyanobacteria are what people commonly think of when they hear cyanobacteria bloom. They can look different depending on the size of the bloom and species of cyanobacteria. They are most likely to form in warm, slow moving water like lakes and bays, and may produce toxins.

How to spot a cyanobacteria bloom:

Blooms most commonly look like green or blue-green scum along the surface of the water. If the bloom is very thick it may appear as though paint or hydroseed has been spilled on the water. Wind/waves can cause blooms to accumulate at the shore.

When the bloom is just forming, or wind/wave action has dispersed the bloom, the water can appear as cloudy or clear water with small green or blue-green globules (balls) or flecks suspended in it.

Fresh blooms can smell like freshly cut grass and older blooms can have a foul smell.

Blooms can appear and disappear quickly or overnight.

Cyanobacteria can move up and down in the water column to find the best nutrient and light conditions. Even if a bloom is not floating on the surface, it doesn’t mean one is not present. Always check the water before entering.

If you see a bloom, do not swim or engage in recreational activities that may involve contact with water in areas where blooms are present.

Benthic cyanobacteria:

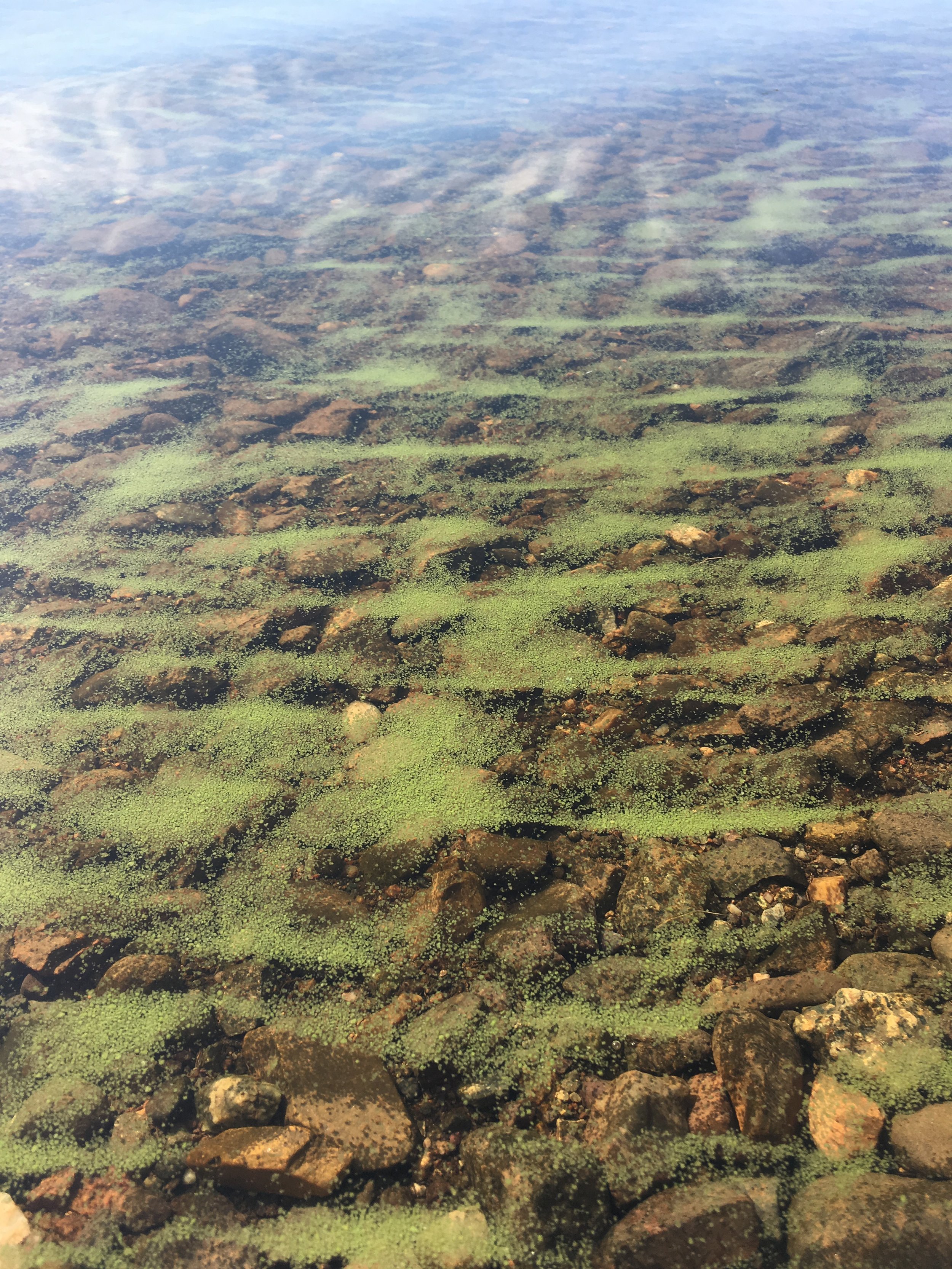

Benthic cyanobacteria form mats along the bottom in both rocky and muddy habitats of flowing streams and rivers. These mats are made up of a mixture of cyanobacteria and other microorganisms. So far, benthic mats have only been found in the main stem of the Wolastoq/Saint-Jean/St. John River. Unlike a surface bloom, these mats can be present in water that looks completely clear.

Dogs are attracted to the scent of decaying mat material and are at a greater risk exposure to toxins as they are more likely to ingest fatal doses. Human poisonings from benthic mats are unlikely.

How to spot a benthic mat:

Mats are clumps of vegetation that can appear as a scum on rocks, mud or other vegetation along the bottom of the stream or river. They can be dark brown, black or dark green. Most of the mats observed so far in the river have been brown with tinges of green or yellow.

Mats under the water will often have many tiny bubbles on them.

When they break off and float to the surface, the bubbles disappear, and can appear spongy.

On the shoreline, mats become dry and can appear light brown or grey. Dried out, washed up mat material may still contain cyanotoxins.

When mats grow in excess, parts can break off from the bottom, float in the water column and wash up on shore making them accessible to children and pets. Carefully watch children and pets to ensure they do not play with or ingest pieces of benthic mats or plants found floating or washed up along the shore.

A piece of benthic mat that has broken off and floated to the surface.

A piece of recently washed up mat material.

Below are some resources available to help with identifying cyanobacteria.

Printed copies of both handouts are available by contacting the ACAP office (office@acapsj.org)

Click the image above for a printable handout on blooms and mats.

English field guide to identifying cyanobacteria. Click the image above to see the guide.

Click the image above for the bilingual visual guide for cyanobacteria and other common aquatic plants.

French field guide to identifying cyanobacteria. Click the image above to see the guide.

If you suspect a bloom or mat, contact the New Brunswick Department of Environment and Local Government Regional Office for your area:

Region 1 – Bathurst (506) 547-2092

Region 2 – Miramichi (506) 778-6032

Region 3 – Moncton (506) 856-2374

Region 4 – Saint John (506) 658-2558

Region 5 – Fredericton (506) 444-5149

Region 6 – Grand Falls (506) 473-7744

Risks and Advisories

Reduce the risk for you, your kids and your pets

Always check the water before swimming for surface blooms and mats.

Avoid swimming or engaging in other activities that may involve contact with the water when blooms or mats have been observed.

Watch children and pets closely to ensure they do not ingest water or play with mat material when swimming or wading.

Avoid cooking or drinking with untreated river or lake water – even boiling water will not remove cyanotoxins.

Do not swim if you have open cuts or sores.

Shower shortly after swimming.

Always wash your hands before eating.

Report any suspected bloom to your New Brunswick Department of Environment and Local Government Regional Office.

Pets

Dogs are attracted to the smell of benthic cyanobacteria mats and are much more likely to ingest mat material and/or drink large amounts of river or lake water than humans.

REDUCE THEIR RISK:

Make sure your dog is well-fed and hydrated before taking it swimming.

Bring fresh water for them to drink.

Watch your pet closely when in the water or along the shoreline to make sure they do not eat any vegetation.

Do not let your pet drink any discoloured water.

After swimming, rinse your dog with clean water and dry it with towels.

Restrict the amount of time you let your dog swim or play in the water – it takes less toxins to cause health problems for smaller dogs than larger dogs.

Consider letting your dog play at home in a kiddy pool filled with clean water if you are in an area known for benthic mats or surface blooms.

To learn more about identifying blooms and mats and reducing risk, check out this video:

Click here for French video!

Advisories

The New Brunswick Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health will issue an advisory when a cyanobacteria bloom has been documented in a waterbody or for water bodies with an established history of blooms (previous confirmed blooms). Once issued, an advisory will remain in place for the season due to the unpredictable and quickly changing nature of blooms. Blooms are highly affected by wind and waves, so they can move or dissipate with changing weather. Due to the potential of future blooms, a location will be remain on the advisory list indefinitely to remind people of the risk.

Even if it is not known if cyanotoxins are being released, an advisory is always issued because of the health risks they present.

Advisories for cyanobacteria or “blue–green algae” have been issued in the past throughout New Brunswick and can be found on the Government of New Brunswick’s advisory website.

The following is a list of waterbodies that have had a confirmed past cyanobacteria sighting from the advisory list. For the most current list, please see the Government of New Brunswick’s advisory page.

Lake Utopia

Chamcook Lake

Lac Baker

Lac Unique

Camp Lake

Bathurst Lake

Harvey Lake

Grand Lake

Washademoak Lake

Wheaton Lake

Lake Nictau

Mactaquac Main Beach

Urquhart’s Cove (Belleisle Bay)

Caron Lake

Yoho Lake

the St. John River from Fredericton to Woodstock

Darlings Lake

California Lake

Blue Bell Lake

Kennebecasis River (Kennebecasis Island to Darlings Island)

Trout Creek

Additional advisories have been issued for two reservoirs in the Moncton area (Irishtown Nature Park and McLaughlin Reservoirs)

Surface Bloom

Benthic mat

Just because these waterbodies are on the advisory list, it does not mean there is always a cyanobacteria bloom or mat present. They remain on the list to remind users of potential reoccurrence and to look for blooms and mats before entering the water.

Frequently asked questions

-

If you have been exposed to cyanobacteria either in the water or mat material, as a precaution, you should remove affected clothing and shower with clean water as soon as possible. If you are showing symptoms, seek medical advice immediately.

-

Dogs are attracted to the smell of decaying benthic mats and should not eat mat material or plants found near the shore as a precaution. Cyanotoxins can be fatal to dogs if ingested. Signs of cyanotoxin poisoning in dogs include seizures, panting, excessive drooling, diarrhea, disorientation, vomiting, respiratory failure, liver failure and death. Death, due to respiratory failure, from anatoxin-a poisoning can occur within minutes to hours of exposure. Death, due to liver failure, from microcystin poisoning can occur within days of exposure. If you suspect your pet has come into contact with cyanotoxins or is showing any signs of exposure you should contact your vet immediately. Most vet offices have an emergency phone number to call after hours if needed.

-

Fish caught in an area experiencing a surface bloom should have all internal organs removed and the fish should be rinsed with clean drinking water before cooking and eating.

-

RPC offers cyanotoxin and total cyanobacteria testing in New Brunswick. However, caution should be taken when sampling an area for cyanobacteria or cyanotoxins to protect the sampler. It should also be noted that this sampling represents a single point in time and toxin production and release is extremely variable and can happen at any time therefore using this to determine if a waterbody is safe or not off of a single sample at one time point is not reliable.

-

Reduce the use of phosphorus on your property by limiting the use of fertilizers and cleaning products that contain phosphorus.

Reduce runoff into waterbodies and prevent erosion by creating or protecting buffer areas between your lawn and watercourses. Plant native trees and shrubs

Install rain gardens and rain barrels to reduce over-land runoff

Properly maintain septic systems and ensure they are located far from the shoreline

Not use herbicides, especially near the water

Get involved with your local lake or watershed organization